Historical Status of Women

The cultural life for the people of the Marshall Islands has always been in a state of transition since culture, traditions, and concepts change according to circumstances and need. It is most likely that before foreign contact the change was very slow and gradual. With initial contact on a more or less regular basis beginning in the mid-1800’s what would be considered traditional confronted head-on the historical events that have occurred ever since in our islands. Mainly as a result of foreign contact and influence, the culture of the Marshall Islands has gone through many stresses and strains over the last 150 years or so. The prevalence of wars and battles fought among the Irooj (Chiefs) for dominance over land, which has always been matrilineally controlled by the women, ended with the impact of Christianity. With this one major change the priorities and concepts of life were greatly altered. Since the greater part of the wars mainly concerned the men, with support and help from the women, many of the major duties and responsibilities of the men were drastically changed in a short period of time. As for the women, their main role as the nurturer, provider and caretaker for their families, did not as rapidly change.

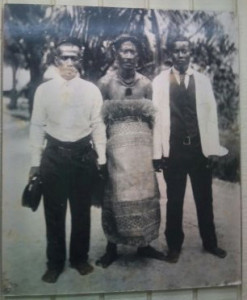

Today the oldest memories of the elders reflect the culture at the turn of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries when the traditions had already been greatly influenced by outside contact and especially Christian missionaries.

Traditional Roles of Women

Major traditional roles of women in the Marshall Islands are still recognized even if not fully practiced. This sheds light on the importance of these roles played in the society of the past and reflects the sustaining significance of identity these roles may still give to women today.

In the traditional way of life the status of women in the Marshall Islands was always one of great respect. The recognition of the woman as the foundation of one’s family, lineage and clan placed her in a position of great importance and potential influence. The following are the five widely acknowledged traditional roles of women that are still recognized today.

- “Jined ilo Kobo” – Nurturer –

Women are still recognized as the giver and sustainer of life, especially in relationship to children. The women are considered the nurturers of all peoples, as women in the traditional stories were the ones who established new clans (jowi) and new lineages (bwij). “Jined ilo Kobo” literally means that a woman holds her child close to her breasts for warmth and protection. It was believed that if a mother held her child close and guided every aspect of its development, the child would grow up with good qualities and be an upright and good person. The child would receive strength, love, and happiness if the mother kept her child close to her breast and gave it warmth and love.The “Jined Ilo Kobo” was the highest position in the traditional culture, and all women attained it who had children and raised her children correctly. Women who were unable to have their own children always adopted and raised these children as their own. Also, a woman would be considered a mother to her sisters and brothers children thus every woman in the Marshall Islands could attain the status of “Jined Ilo Kobo.”“Jined” means our mother, and “Kobo” refers to the idea of preserving, preparing, shaping, safekeeping, protecting, as well as warmth from the mother’s breast. “Jined Ilo Kobo” means the very root of the family – your caretaker, your nurse, your doctor, your teacher, your social worker…she is always there and available when you need her. She shapes your future.

- “Lejmanjuri” – Peacemaker –

This woman was usually the oldest women of her lineage or within the immediate family. In dealing with family problems it would be the oldest daughter (manje) who would be the “Lejmanjuri”. During times of warfare, when one Irooj (Chief) would fight another Irooj for power, land and prestige, the Irooj’s oldest sister (either older or younger than he), or oldest female parallel cousin from his mother’s lineage could stop the warring by telling her brother to stop. The Irooj had to listen and obey this sister because she was “Lejmanjuri”. Also in times of warring, if the Irooj of the losing side came to the “Lemanjuri” of the winning side and asked her to stop the fighting she would then tell her brother who would be the Irooj of the winning side to stop and he would obey her request. Both Irooj would have sisters who could be “Lejmanjuri” and these sisters of the two opposing Irooj could also decide to end the warring. It is assumed that the “Lejmanjuri” exercised this right when the fighting became overly destructive and bloody, thus the woman was protecting, and holding her people together. Today since there is no longer warring the “Lejmanjuri” possibly acts as the final decision maker for her family or lineage, especially in circumstances concerning land that is passed matrilineally.The word “Lejmanjuri” comes from two words – “lejman” and “juri”. “Lejman” means the woman who was born ahead of all the rest of the children in a family, especially born ahead of the men. “Juri” literally means to step on. So in general, the term “Lejmanjuri” refers to the power invested in this first-born female that enables her to stop any quarrels, fights, or even battles that occur between brothers, their families, and their clans. The word “lejman” can be further broken down into two words – “lej” and “man”. The word “lej” means strong, aggressive, physically domineering, and the word “man” means first or before or ahead. So a woman who is the “lejmanjuri” is looked to for strength and wisdom in making decisions.

- “Kora Menunak” – Benefactress –

The word “kora” means woman. “Menunak” is a word used for specific types of birds particularly the frigate bird. “Menunak” refers to the feeding pattern of birds – they fly out, fish and fly back to their nests and their young with good things. Usually when a woman marries, the family gains a son, and does not lose a daughter. Wherever she goes, within her atoll, within or outside the Marshalls, she is always going to reap benefits for her family because she will always be concerned for her family – parents, brothers, sisters, etc. Many Marshallese women have married outside the Marshalls and this brings benefits to the islands because these women will always be concerned for their family and relatives and will help them in any way they can. This traditional woman’s role infers that the woman will always care for and never forget her family. She has to care; she is the foundation of her family. - “Limaro Bikbikir Kolo eo” – Encourager –

“Limaro” means those women, “Bikbikir” means to shake, to beat, to vibrate, and “Kolo eo” means the spirit, the enthusiasm, and the charisma. Long ago when the men went to their battles, the women would be in the boats accompanying them and beating the battle drums. Also after the completion of carving and the building of an outrigger canoe when the initial launch was made the women would chant their incantations to move the men or to condition their minds and bodies for the difficult task of rolling the canoe to the water. Today when baseball or other sport events occur, the women and girls are prominently encouraging and recognizing the successful accomplishments of a game by singing, dancing around, yelling, and beating on any available object. The pictorial illustration of the word “bikbikir” is that of shaking a piece of cloth. If you shake one end it will move forward. To these days, during political campaigns especially, men have come to rely on women’s organizations and groups for the planning and implementation of their campaign platforms and rallies. This expression also infers the idea of women challenging any discouraging agent present in their men and encouraging the men at the same time to over come the difficult task they are confronting. - “Kora Jelton Bwij” – Unifier of a Lineage –

As stated before “Kora” means women, “jelton” means to untie or tear apart, and “bwij” means lineage. The “kora jelton bwij” has the power to hold together her family lineage. Usually this woman is the oldest woman of her lineage and if someone in her lineage does something against the wishes of the Irooj (Chief) or Lerooj (Chieftess), she would be the only person from whom the Irooj would accept an explanation or apology. Also if there is disruption in a lineage she makes the final decisions in order to solve the problems of dissension. In times past it was believed that the “Kora Jelton Bwij” had the power, knowledge, and ability to perform certain acts of sorcery or magic which could weaken the influence of and harmony among the people of her husband’s lineage if she thought her husband was not caring enough for his own children, but carrying more for the children of his sisters. Although acts of “magic” are still performed today, the belief in power of such acts is questioned by many.

Traditional Restrictions on Women

Along with the above highly respected traditional positions of women in Marshallese culture, there have also been great restrictions placed on them. At the turn of the century most women were still confined to their home and immediate surroundings. Often they were not allowed to visit other households nor become involved in community decisions and discussions. As stated in the chapter on land, anyone who was the oldest member of his or her lineage could be the alap, but the woman who was alap usually designated her younger brother or possibly son to exercise this power. In the same instance a woman who was Lerooj (Chieftess) would pass the real power and decision-making to her younger brother or possibly son. Therefore, even with acknowledged high birth or position, the women’s role was most likely secondary to the men’s. It may be assumed, however, that at least some women exercised their power of alap and Lerooj, and authority over the matrilineal land base.

Today it is often acknowledged that women are not supposed to be canoe builders, navigators, or fishermen. But in light of oral literature available, there were women navigators, canoe builders, and fisherwomen of the past. Their names are still often known along with their lineages. It is possible that the restrictions and gender role divisions were more sharply defined after the domineering influence of Christianity, which taught and propagated the role of the woman which prevailed in late 19th century Europe.

It has also been expressed by some older women of today that the Marshallese woman became more subordinate during the Japanese occupation of these islands, due to the expectations reflected by the Japanese men and particularly the manners and behavior displayed by the few Japanese women who resided in the Marshalls.

With this brief overview we may conclude that the culture evident today has maintained major characteristics of what we know existed over a hundred years ago, but numerous influences and changes occurred before the extremely rapid changes since the end of World War II.

You must be logged in to post a comment.